The Brics don't stack up as a committee to run the world

Receive free G7 updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest G7 news every morning.

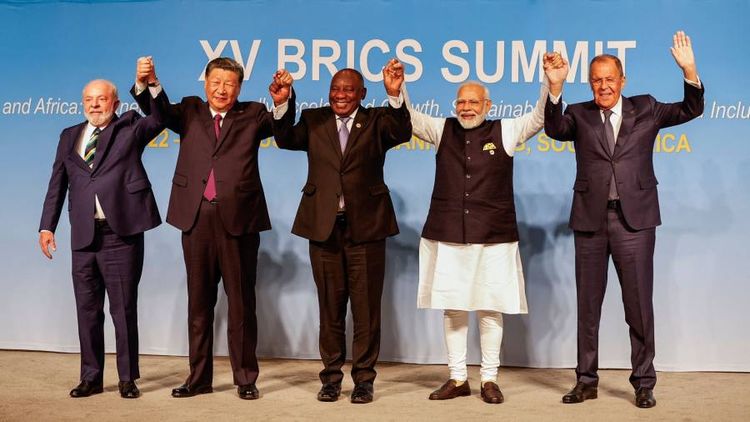

For evidence that Brics summits are adopting the routine features of the global governance circuit, observe the familiar jostling during this week’s meeting in South Africa to manufacture an announcement and maintain the impression of forward momentum.

The closest to a “deliverable”, to use the familiar grating term, is a commitment in principle to expand the grouping’s membership beyond the current five (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Even that’s uncomfortable for India and Brazil, which are concerned about accepting more members strongly aligned with China.

The Brics’ weaknesses as a policymaking forum are evident. The club has insufficient unity of purpose and little ability to enforce decisions. But the difficulty of maintaining coherence within an informal grouping is hardly new. The Brics’ incumbent rival — the G7 club of rich countries for decades regarded as a steering committee for the world economy — has also often struggled for consensus.

Effective international institutions fulfil various functions, including as a repository of specialist knowledge or powers and a means of setting and enforcing rules. Properly employed, the last of these means that collective decisions can weigh heavily in their members’ domestic policymaking debates.

Among formal institutions, these attributes are clear, though inevitably constrained by their shareholder governments. The IMF, for example, has specialised knowledge of financial crises and a rapid rescue lending capacity. It attaches conditions to those loans such as rapid fiscal tightening, the imperative of meeting which helps borrower governments resist domestic opposition to sometimes wrenching change.

It’s harder to discipline members within informal groupings. The G7 built a reputation in the 1990s and 2000s as a steering group for institutions such as the IMF. But while it could agree on imposing tough fiscal and deregulatory conditions on borrower governments and move quickly to solve systemic problems, such as the Asian and Russian financial crises of 1997-98, it had more problems constraining its own members.

Even the heyday of the G7 was marked by continual conflict over structural economic policy and exchange rates. France, tired of continually being bullied by the US into pledging economic deregulation, in 2003 brilliantly sabotaged its commitments by employing a creative translation of a G7 communique into French, promising the cuddlier “réactivité” rather than the harsh “flexibilité” (“flexibility” in the original) that Washington had demanded.

While the G7’s predecessor, the G5, had successfully orchestrated a weakening of the dollar in the Plaza Accord of 1985, there was tension between Tokyo and Washington (particularly Capitol Hill) in the 1990s and 2000s about Japan holding down the yen.

Washington also complained that its more general campaign against exchange rate misalignments and current account imbalances in the 2000s and 2010s, largely aimed at China, was undermined by Germany’s export obsession. In both cases, G7 solidarity was less important to Japan and Germany than protecting their growth models. The G7 was also largely absent during the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, the EU insisting that European governments design the rescue packages.

True, the G7 has acquired a new sense of purpose after Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, co-ordinating sanctions and capping the price of Russian oil. But it is no longer economically big enough to cripple Putin’s war effort, and nor is it united around US proposals for more aggressive measures against Russia such as a broad export ban.

Brics has the G7’s problems and then some. It is notoriously geopolitically divided, India’s strategic rivalry with China weakening it as a forum for trade and regulatory policy. The EU (whose three largest economies are G7 members) and the US, despite different approaches to data privacy, have worked diligently to mesh their digital economies through data-sharing agreements. By contrast, India in 2020 unilaterally banned 59 China-based apps including TikTok and WeChat, declaring them a security threat.

The Brics’ general moaning about US hegemony, including complaints about the rich world’s control over the international financial institutions, doesn’t extend to a coherent plan to replace it. Each time a new head has been appointed to the IMF or World Bank, Europe and the US respectively have maintained their traditional lock on appointing one of their own because low- and middle-income countries have never been able to unite behind a challenger.

Neither India nor China has ever pushed a credible candidate to run either institution: although World Bank head Ajay Banga was born in India, he is a US citizen and was nominated by Joe Biden. There is not enough trust between New Delhi and Beijing to put one of the others’ officials in charge. Meanwhile, Brics’ collective development finance institutions such as the New Development Bank are tiny next to China’s vast bilateral lending programmes.

Enlarging a grouping does not automatically make it more powerful. The G20, which largely replaced the G7 as the world’s foremost economic policy forum in 2008 during the global financial crisis, is beset by entrenched differences. Consensus cannot be reached purely by fiddling with structures or expanding membership. A global steering committee needs to start with internal consensus. For the Brics, so far that’s largely absent.