IN FOCUS: Turning tides for Malaysia's fishing industry over climate ...

KUALA LUMPUR: As Mr Chia Mui Seng removes a sheet covering his unused fishing nets, he discovers a huge colony of ants that has made a nest in them.

Having not gone out to sea for four months now, Mr Chia sporadically checks on his fishing equipment that he has left behind on his boat in the coastal town of Sungai Besar, Selangor, a two-hour drive from the glittering capital city of Kuala Lumpur.

The nets must be properly covered, the fisherman told CNA, or risk being nibbled and damaged by rats.

“(But) it has been so long (since I last checked my equipment) that the ants are making their nests here,” he said.

Mr Chia, who said that he used to be able to net up to 20 tonnes of fish in a month, claims that he has not gone out to sea because there was not much to catch these days.

“Last time, I used to give people fish but now I have to buy it for myself,” he said, noting how the tides have turned on him.

“If I go out, I will lose a lot of money, much more than I am already losing now.”

The vessel Mr Chia operates when out at sea needs a crew of 18 men - all of whom have to be paid for their work. With dwindling catch and an uncertain future in the industry, the veteran said that he had no other choice but to let go of his workers.

“Many of the other fishermen from here are saying that they are coming back empty-handed from sea,” said the 56-year-old, who starts his boat every day just to keep the engine in working condition.

While Mr Chia admitted that it was normal in the past to have some seasons where the fish stock is less, this time it “seems different”, noting his four months of absence from the sea.

He does not appear to be the only one in Sungai Besar who is affected by the declining catch.

Kampung Bagan village chief Sia Chock Sung, who is a fish wholesaler, told CNA that the fishing industry in the town has been badly affected.

“This has been a bad year for everyone. It’s much harder to get fish stock,” he said.

WWF-Malaysia, citing a Malaysian government survey, warned that the country’s waters were “severely overfished”.

“Results from the last trawl surveys carried out by the DOF in 2016 indicate that demersal fish biomass and densities have dropped by 88 per cent from the virgin stock for the whole of Malaysia.

“The Director-General of Fisheries also revealed … that we have lost 96 per cent of our demersal fish stock to overfishing in less than 60 years,” the environmental protection organisation said in a statement to CNA.

The situation in Sungai Besar might be a harbinger of things to come for the fishing industry in Malaysia, with many worried about their livelihoods as they say that catch has generally declined over the past several years.

This, too, has led to customers paying more for the popular source of protein, in tandem with the declining catch.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), fish is a major protein component in Malaysians’ diets, with the country ranked as one of the highest consumers of fish and seafood in the world at 53.3kg consumed per capita in 2020.

As a whole, the fishing industry in Malaysia contributed 0.8 per cent or RM11.5 billion (US$2.5 billion) of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022.

One of the biggest challenges that the industry is likely to face is the rising threat of climate change, experts have noted. But beyond that, overfishing is also believed to have caused marine resources to dwindle.

Malaysia’s Department of Fisheries (DOF) told CNA that while the supply of marine resources is “stable” for now, it recognises that there is concern over the sustainability of the industry in view of the threat of climate change and overfishing.

Beyond that, there are issues such as a lack of manpower within the fishing industry and the intrusion of foreign fishermen into Malaysian waters that have impacted the catch for local fishermen.

And as an exporter of marine products - which includes fish - to countries like Singapore, China and Japan, the dwindling catch might spell further trouble for the industry.

In 2022, Malaysia’s exports of marine products was worth RM4.21 billion, climbing steadily from 2017 when exports then totalled RM3.16 billion. Its biggest marine exports were shrimps and squid as well as mackerel and barramundi.

According to DOF statistics, the number of fish caught fluctuated between 2006 and 2016. But since then, the number has dropped gradually except for a slight uptick in 2019.

In 2016 - a good year - the amount of fish caught from the sea was 1.57 million tonnes. In 2022, however, the fish catch amounted to 1.31 million tonnes - a drop of about 16.5 per cent from 2016.

DOF director-general Adnan Hussain told CNA that fish landings - defined as the catches of marine fish landed in foreign or domestic ports - for most years were consistent except for the C2 zone.

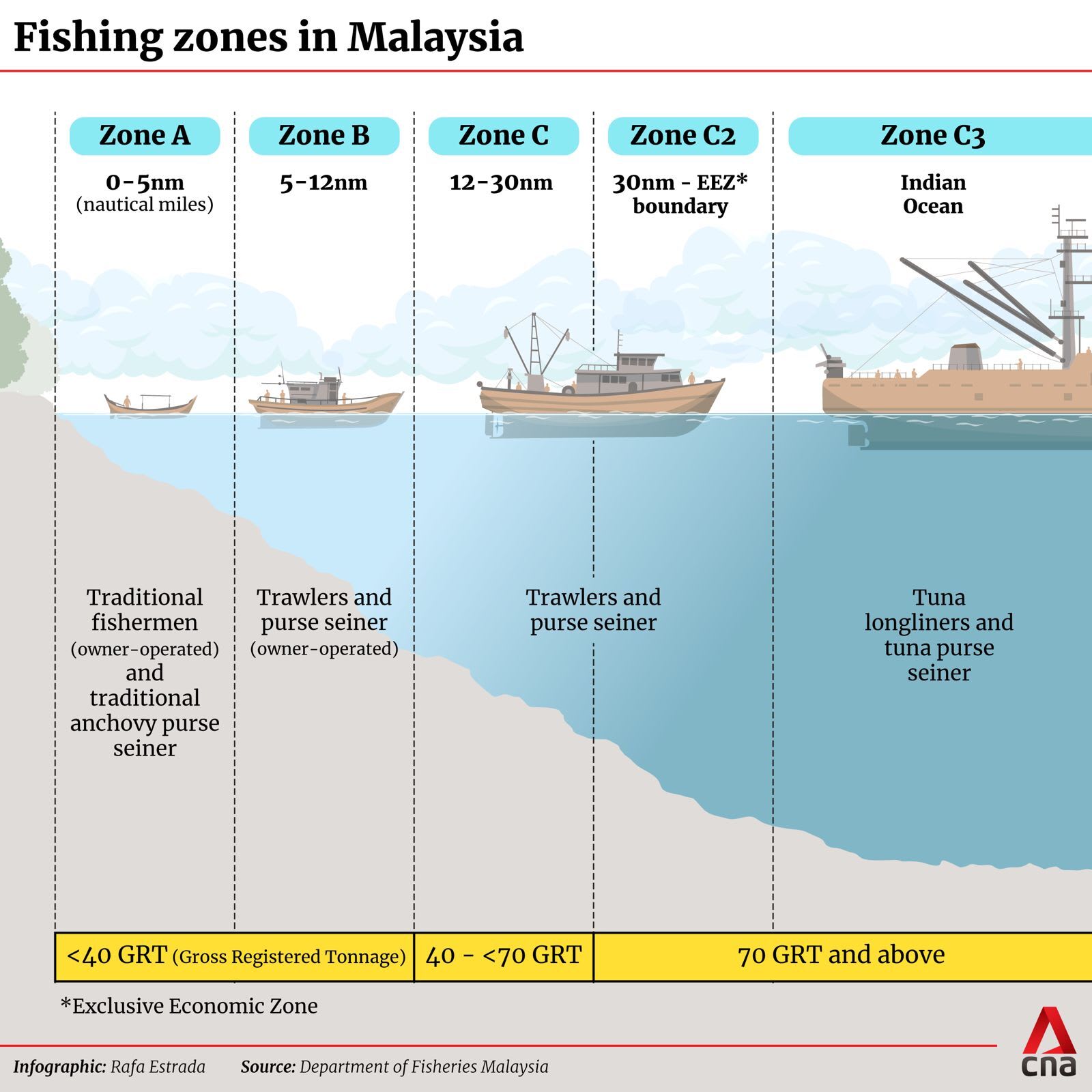

In Malaysia, fishing is classified according to zones: A (0-5 nautical miles), B (5-12 nautical miles), C (12-30 nautical miles), C2 (30 nautical miles to the border of the open seas or exclusive economic zones) and C3, which is the Indian Ocean.

Mr Adnan said that other factors that have caused the drop in fish catch include the intrusion of foreign fishermen, with losses estimated to be between RM3 billion and RM4.25 billion yearly.

“We target about 1.3 million tonnes a year because that is based on the capacity of our resources and our fisheries stock. This is a sustainable figure,” he said.

“If we increase the fishing activities, we might get more fish for a few years but it won’t be sustainable in the long term.”

DOF's 2022 annual report noted that though the amount of catch in 2022 was lower than the previous year, its value rose to RM11.3 billion from RM10.8 billion in 2021.

“This might not be popular among the consumers, but the good thing about the industry is the government does not control the prices of fish … This means if (operation) costs go up, so does the price of fish. It depends on demand and supply,” said Mr Adnan.

According to data from the website of Malaysia’s Fish Development Authority (LKIM), the average prices of 20 most popular species of fish in the last week of 2022 and 2023 did not differ by much.

It is noted, however, that the prices of some types of fish were more expensive in 2023 as compared to the year before. Conversely, some fishes were cheaper last year as compared to 2022.

For example, the silver pomfret fish cost RM51.68 per kilogram in 2023, up from RM47.55 per kilogram from the year before. Meanwhile, mackerel was cheaper at RM28.75 per kilogram last year as compared to RM29.24 per kilogram in 2022.

Fishmongers at the Meru Market in Klang told CNA that the prices of fish depends on its availability and demand.

Mr Mohd Azizul Sabri, 46, said that the cost generally goes up during the rainy and festive seasons, which he attributes to a matter of “demand and supply”.

“There are times when you can get them for cheap prices. Suddenly the volume (of fish) is a lot and we have to get rid of them (and sell to customers) in two days,” said Mr Azizul, who has been in business for the past eight years.

Meanwhile, fishmonger Lim Eng Hooi, 66, claimed that there was a surplus of fish in the market at the moment, but there were not many people buying them.

“If there is no fish, the prices will go up. If there is a lot, the prices will go down. It’s a common thing with fish,” he said, adding that the availability of a certain species also depended on the season.

Generally, Mr Lim said, bred fish - which refers to those that are commercially farmed - are easier to procure as compared to those caught at sea.

In Sungai Besar, fishermen such as Mr Mispan Sarikin found themselves being adversely affected by dwindling catches.

The 59-year-old told CNA that he had downgraded from owning a vessel with his own crew members a few years back to a smaller boat because his catch was becoming irregular.

“Our catch is becoming less and less all the time,” he said, although he could not give a reason why this was the case.

If he were lucky, Mr Mispan said that he is able to bring back 20 to 30 kilograms of fish and shrimp from a day’s work. But there are days, he lamented, that he would return home with nothing.

“I would not encourage anyone to be a fisherman because there are a lot of uncertainties when it comes to what you will be able to catch,” said Mr Mispan, who has been a fisherman for almost 40 years.

CONCERNS ABOUT MANPOWER AMONG LARGER FIRMSFor firms that own larger boats that can go out further to sea, the problem appears to be a lack of manpower to staff the fishing expeditions.

Mr Chia Tian Hee, the president of the Fish Association, told CNA that there were still fishes in the sea but a “very big problem” faced by the industry was the operations by the authorities against undocumented foreign workers.

There are an estimated 150,000 people including 116,000 fishermen who are involved in the Malaysian seafood industry. However, there appears to be no concrete numbers on those who are undocumented.

“The boats are not going out because the operators are afraid of the raids on them,” Mr Chia said, adding that many of the workers were foreigners.

According to the DOF, foreigners made up 25 per cent of fishing crew in 2022 and are only allowed to work on fishing boats that operate in Zones C, C2 and C3 out at sea.

Mr Chia further claimed that there was more bureaucracy when it came to applying for permits for these foreign workers.

“Many fishermen are crying now. Even if they wanted to sell off their boats, no one would want to buy them. Some of them are not able to pay off their loans,” he said.

LKIM chairman Muhammad Faiz Fadzil told CNA that about 36,000 fishermen who are considered to be in the lower income (B40) group in Malaysia get an RM300 allowance monthly.

LKIM is a body that was established to primarily look into the welfare of the fishermen.

“We have to change their mind and attitude to transform them from fishermen to entrepreneurs. That will change their socio-economic situation,” he said.

Mr Adnan of the DOF said that climate change could have an enormous impact on the industry, thus affecting the yield for Malaysian fishermen.

“Weather changes such as high winds, heavy rains, high waves or change in temperature of water can affect the behaviour of the fish and their locations.

“This makes it more difficult to catch them as they are likely to move to deeper or more sheltered waters,” he said.

Marine ecology lecturer Dr Wan Mohd Syazwan of Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) said that while there has been a decline in the catch of commercial fishes over the years, the trends vary in different geographical regions.

He said that the fish most likely to be affected from the effects of climate change are the demersal fish - those that are associated with the bottom of the sea.

Very dependent on coral reefs, these include the grouper, sea bream, and snapper.

“The corals which are a habitat for these fish are also affected by climate change. Demersal fish are less resilient to unfavourable environments, compared to pelagic fishes (those that are associated with the surface of middle depths of a body of water),” Dr Syazwan said.

The pelagic fish - he noted - had been shown to respond to climate change by migrating towards deeper waters to maintain optimum conditions for their growth, reproduction, and survival.

Types of pelagic fish include tuna, mackerel, Spanish mackerel, yellowstripe scad and sardines.

As fish populations re-distribute in response to changes in habitat conditions, Dr Syazwan said that fishermen may need to travel further to find their target species, shift to catching different species, or invest in new gear.

Professor Mazlan Abd Ghaffar of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu’s (UMT) Institute of Marine Biotechnology said that unregulated entry of fishing gears both for demersal and pelagic fishes can undoubtedly result in overfishing.

He warned that demersal fish stock was decreasing due to deployment of destructive fishing gears such as otter trawls.

“Indications of decrease in demersal fish stock can clearly be seen when on average much smaller fishes land over time and years,” he told CNA.

The FAO estimates that 35 per cent of fish stocks have been overfished.

Mr Adnan from the DOF claims that there is no over exploitation of fishing in Malaysia, but that several zones have already achieved the maximum sustainable yield (MSY). This refers to the theoretical highest catch that a fish stock can support in the long-term if environmental conditions remain.

Mr Adnan said that in the Straits of Malacca, most of the sources are at MSY level while in the east coast, there is still an overstock of fish.

He also noted that demersal fishes are caught by Malaysian fishermen using trawlers and traps that may destroy the habitats of these fishes.

"The use of trawlers is not very friendly to our resources because they tend to destroy habitats. That’s why there is some pressure when it comes to demersal fishes in the west coast,” he said, noting that the state of Selangor has experienced a decline in fishes caught in the past year.

Mr Adnan added that the DOF is not issuing anymore fishing licences for zones A, B, and C but are still issuing C2 and C3 licences. He noted that there is a “lot of potential” for deep sea fishing in these areas, though it requires a higher capital for operations.

“Deep sea fishing only contributes 16 per cent to the total fish landings,” said Mr Adnan, adding that the authorities were encouraging more operators to take up the C3 licenses in the Indian Ocean in order to increase the fish yields.

The Indian Ocean is said to account for 20 per cent of the world’s production of tuna.

For now, he said that the department has a quota of 70 vessels for the C3 licences, though only 11 of them were taken up for the time-being.

Mr Adnan said that moving forward, there is more of a push towards the aquaculture sector, where the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security is targeting for it to contribute 60 per cent of the output compared to 40 per cent of the marine catch.

Currently, aquaculture - which refers to the breeding, raising, and harvesting of fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants - contributes only 30 per cent of the output.

But the amount of catch by aquaculture has increased by 37.5 per cent from 417,000 tonnes in 2021 to 574,000 tonnes the following year.

The value of the aquaculture industry also grew from RM3.43 billion to RM4 billion in those years. “We target for the catch from the sea to remain at the same rate, but for the harvest produced by aquaculture (to) increase at the same time,” said Mr Adnan, adding that they are targeting for the sector to contribute 958,000 tonnes of output worth RM7.1 billion by 2030.

Malaysian Fisheries Society president Dr Noor Amal Azmai told CNA that the growing demand for aquaculture was due to the need to improve food security in the country.

“The government is doing a lot of research on improving or increasing aquaculture from fish, shrimp, molas, and crustaceans. This means you can culture your own food and do it anywhere,” he said.

The saltwater fish that are commonly bred using aquaculture include snapper, seabass, and grouper while for freshwater fish this would include tilapia, catfish, and patin (striped catfish).

“Generally, the fish in the ocean are decreasing and that’s why we need to culture our own food. We are not nomads anymore and cannot fully depend on the wild,” he said.

Dr Noor Amal, however, said that cost to sustain aquaculture may fluctuate from time to time, noting that the war between Russia and Ukraine has caused the price of wheat - which is an important component of fish feed - to increase.

“About 60 per cent of the cost alone is fish feed that we fully import,” he said.

WHAT CAN BE DONE NOW?Dr Syazwan of UPM said that efforts to jointly mitigate the effects of climate change as well as the reduction of fisheries exploitation are “critical” to ensure the sustainability of fish stocks in the future.

He stressed that there was a need to control fisheries exploitation - such as through the type of equipment used - and suggested that smart spatial zones be implemented to limit fishing activities in areas that are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

“It is important for enforcement to be strengthened to control the overexploitation of fishing,” said Dr Syazwan.

Meanwhile, Mr Adnan of the DOF said that his department has been building artificial reefs at different locations around the country, with about 1,800 installed at more than 100 locations since 2016.

"These reefs help conserve marine resources by creating new areas for the growth of corals. This helps provide breeding areas for fish and other marine life, helping create new habitats and protected areas," he said.

Beyond that, Mr Adnan said that the authorities have limited the catch for certain types of fishes to a particular season, such as the case of anchovies that are caught off the coast of Langkawi.

WWF-Malaysia told CNA that stakeholders in the fisheries and seafood industry need to work together to promote sustainable fisheries that emphasises the need for a science-based fisheries approach to sustain the marine resources.

The organisation said that this can be done through stock recovery, establishing a commercially and ecologically viable fisheries industry, while also protecting the fishing communities’ livelihoods.

“The seafood supply chain needs to reform; to adopt digitisation of catch data and traceability systems. Consumers need to rethink the consumption of seafood, to only choose sustainable options, and only choose seafood at a responsible consumption rate,” it said.

WWF-Malaysia warned that the increased fishing efforts over the past 50 years - as well as unsustainable practices in the industry - are pushing many fish stocks “to the point of collapse, with livelihoods dependent on fish adversely affected”.

“Fishers need to put in more effort to catch fish; they need to go further out to sea and spend more time harvesting, and in return they are catching smaller and lesser fish,” it said.

Mr Chia - the fisherman in the coastal town of Sungai Besar - told CNA that should the catch continue to be dismal and the situation persists, he may have “no choice” but to sell his 20-year-old fishing boat at a loss after the Chinese New Year celebrations in February.

He still has debts to pay while two of his children are still studying in university. But he will be in a twist on what he will do next.

“This is the only thing I know and have done since I was young. I never went to school. What else can I do?,” said Mr Chia.